Media Ecology

URGE co-founder Federico Gaggio investigates the field, considering how media contribute to the crises we face, and what a healthy Media Ecology may look like.

Media are so pervasive in our lives that we take them for granted, like air and water. Nowadays, people consume media more than they do any other activity. We may think of media as channels, conduits for 'content' and communications. Print, radio, TV, social. But to think of media in terms of ecology is to consider a much broader set of phenomena. Over the years I have been considering the role media consumption plays in human affairs, particularly in relation to the climate crisis, the mental health crisis, and other crises of values, attention, meaning, democracy… How may it perpetuate causes, and how may it contribute to solutions? These are some of the questions that I want to investigate.

60 years ago Marshall McLuhan set out the foundations for media theory (Understanding Media, 1964). He used the terms media, technology and language more or less interchangeably. While McLuhan paved the way, the term Media Ecology was introduced by Neil Postman, in 1968. Postman defined it as "the study of media as environments".

Ecology and Ecosystem are used as a biology metaphor to illustrate relations between different media 'organisms'. This language seems fitting when asking questions about the role the media play in the climate crisis. But what do we think about when we think about ecology? Eco is derived from the Greek oikos which means house, place of dwelling, habitat. Also the root of the word Economy. Media literacy expert Antonio Lopez observed that the association of ecology and economics for a 'house' makes practical sense, but in a globalised society the notion of household must be conceived on a planetary scale. This is what Buckminster Fuller meant by Spaceship Earth.1

Writing when TV was the dominant medium, Postman argued that traditional education, based solely on written media, was rapidly becoming irrelevant in an age of space travel and nuclear weapons. Postman questioned how our interactions with media facilitate or hinder our chances of survival. His reflections ring remarkably current in our age of existential threats and multiple crises. He believed that people need to become "competent in using and understanding the dominant media of their culture". 2

The Metaphor is the Message

Critical voices in Media Ecology argue that the dominant metaphors of media are still trapped in the flawed assumption that man and nature are separate. Terms like broadcast, field and even culture all derive from agricultural practices.

When media practitioners use the ecosystem metaphor, they are essentially drawing on a nineteenth-century, mechanistic framework of the world. Mechanism is a reductionist model of nature that correlates with the manufacturing process, which views the universe as comprised of atomized parts that work together as one great machine.3

An alternative cognitive model takes the opposite view that people are not separate individual entities, but rather parts of an "interconnected thinking system". British anthropologist Gregory Bateson considers the western civilisation mindset which separates man from nature to be an epistemological fallacy, with potentially catastrophic consequences. Instead of focusing on Man (individuals, households, clans), Bateson urges us to consider the system as a whole, including the environment and all interactions various organisms have within it.4

Daniel Goleman defines Ecological Intelligence as "our ability to adapt to our ecological niche" while considering the hidden consequences — health, societal and environmental, of what we buy and do.5 Environmental education theorist C.A. Bowers argues that the ecological crisis is deeply rooted in collective cultural patterns and language. Western cultural assumptions, particularly those embedded in educational and media systems based on technology and consumerism, contribute to environmentally destructive practices.

Dominant media metaphors (ecology, environment) curiously appear to lack any reference to living systems. The mechanistic model of the world produced a global economy in which actions are constantly taken in the name of growth, regardless of their long-term impact on living systems. Lopez reminds us that in order to address the ecological crisis, it is necessary "to transform our mental models from mechanism to something related to systems thinking and ecological intelligence."

Media Grow Culture

Talking about television, film critic Serge Daney remarked how media reflects societal values and the unconscious narratives within society. Media can be a mirror of society, but it also has the power to shape its culture.

Culture (...) was originally meant to describe a process of cultivating taste. In the most profound but simplest of terms, media grow culture. But there are different philosophies about how to grow, such as monoculture versus permaculture. 6

In his reflection on the evolving nature of television, renowned TV executive and critic Carlo Freccero distinguishes between two alternative philosophies, highlighting their structural differences: 7

TV as education: public service model, whose role is to advance culture, initially the dominant approach in post-war Europe.

TV as commerce: private, for-profit networks, whose role is to boost consumption, initially dominant in the USA.

For Freccero, the two models reflect a fundamental difference in the conception of culture. In Europe, culture is essential, in America, the market is. Commercial media can, and did, provide a level of public service. Not necessarily by emulating the public broadcasters’ (PSBs) educational remit, but by acting as a shared cultural space: "an agorà (public square), a social place of debate and encounter in which life is lived together". This still happens, in the UK for example.

But in Italy, 30 years after Silvio Berlusconi's rise to power, public and private broadcast networks are practically indistinguishable. And not just in Italy. According to Freccero, globalisation flattened everything on the basis of what he calls mono-thought (neoliberal orthodoxy). The remit of a public service is to grow cultural capital, but today economic capital is the only universally recognised value in the globalised world.

Ecological intelligence reveals the intersection and interdependence of our living and media environments. In English the word commons means "a land or resources belonging to, or affecting, the whole of a community". Lopez and others suggest media ecosystems are a kind of cultural commons. Media and living systems are two interrelated commons, a commons defined as, “all that we share.” 8

Monoculture vs Permaculture

The health of cultural ecosystems depends on the attitude we have as a society towards the commons. To continue within the agricultural metaphor, the tension here is not public vs private or education vs commerce, but monoculture (the cultivation of a single crop in a given area) vs permaculture (the development of agricultural ecosystems intended to be sustainable and self-sufficient). The dominant paradigm of separation breeds a 'monoculture of the mind', eliminating the possibility of alternatives to emerge. Exactly like monocultures in living systems reduce biodiversity. Intellectual property is another control mechanism based on “the same beliefs that economy and living systems should be subjected to unregulated markets and privatization”. 9

Monocultures, whether by totalitarian regimes or unfettered market dominance, effectively reduce the space for new varieties to grow, destroying cultural diversity. As Bowers pointed out, cultural commons are constantly under threat of enclosure by unregulated private media conglomerates. The evolution of the media industry through relentless progressive consolidation continues unaffected by regulatory frameworks which are chronically outdated. The growth imperative of capital accumulation encourages media companies to aggregate in giant conglomerates in a race to obtain monopolistic positions. We have seen this over and over again, in all media sectors, publishing, broadcasting and digital alike.

There is a pattern. Companies break through by innovating, in content, technology, or service. They acquire a critical mass by creating value for customers, then shift their focus to delivering audiences to advertisers, and finally — if and when they reach a dominant position — turn to capture most of the value for their shareholders. Cory Doctorow memorably defined this process in the digital domain as "Enshittification".10 Network effects and proprietary ecosystems create high switching costs, making it harder for users to find other options and leave. The crucial struggle that is playing out in the digital sphere is not between the Big Tech giants, but between open-source and closed (proprietary) systems. A proprietary system breeds a monoculture. Open systems are like permaculture gardens.

Grassroots uses of media imply a different model from the dominant approaches (public service and commercial) described earlier. Lopez refers to it as organic media. It's a new form which evolved from the early days of pirate radio, through the explosion of local TV stations in the early '80s up to the recent boom of newsletters, blogs, podcasts, online videos and beyond.

Lopez calls for the "occupation and reclamation of public spaces and the cultural commons" as a form of resistance to the dominance of the monocultures of consumerism and mind control. He does not mean that people should physically occupy the premises of media conglomerates, but rather to reclaim the collective imagination through organic media. On the structural level, I noticed an interesting symmetry between media models (public, commercial, organic) and the structure of modern societies.

Rebalancing Media

In Rebalancing Society, Henry Minzberg makes the case that society has developed an imbalance which could "destroy our democracies, our planet and ourselves". The dichotomies of public/private and culture/commerce in media mirror the tension between the opposite ideologies of government vs market prominence. Western social-democracies managed to find a middle way, combining a good level of public service with a free market. But today the extremes rule: ex-communist countries embraced state-run capitalism while retaining autocratic control. Western democracies became dominated by a similarly monolithic perspective: neoliberal dogma.11

Minzberg argues that challenging this dogma is key to addressing the multiple crises we face. Instead of letting ourselves be driven to "compete, collect and consume our way to neurotic oblivion", he proposes a framework that includes a third actor which needs to be empowered to restore the balance: Civil Society. The operative word is, once more, balance. Mintzberg is not anti-business: he works with and cherishes private enterprises that "compete responsibly" and create value while caring for people and the environment (as do I). He is critical of business that exploits and extracts, leveraging economic and political power to sway opinion and lobby governments to consolidate their privileged positions.

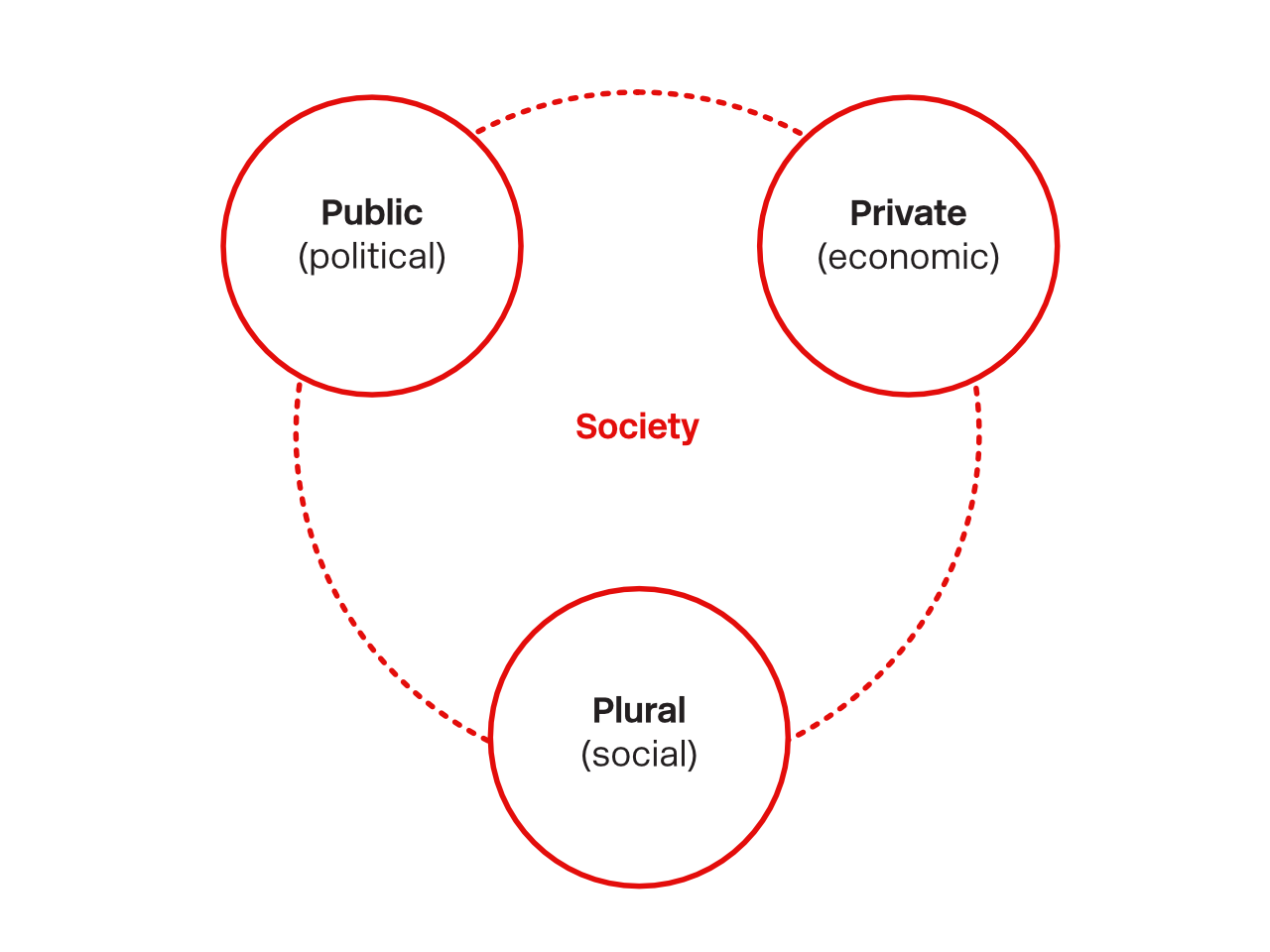

For Mintzberg, restoring balance in society requires moving past two-sided politics and giving equal weight to three sectors: Public (political), Private (economic), and Plural (social), representing governments, businesses, and communities. The plural sector is not a middle way between the other two. It is made of communities, associations, cooperatives, NGOs, religious groups, movements and social initiatives. The critical difference is that none of it is owned by private companies or controlled by the government.

The plural sector is all of us. As citizens in modern economies we need responsible business to provide employment as well as consumer goods and services. We rely on responsible governments to provide protection, healthcare, education and law. We want to participate in thriving local communities where we can connect and belong. Communism and capitalism “each tried to balance themselves on one leg. It doesn’t work.” Social-democracies have attempted to balance on two legs, but they failed as a result of the "politics of compromise", which renders local governments subservient to all-powerful transnational corporate interests.

If we adopt this approach for media ecosystems, I see a clear and obvious symmetry between Public Service Media and Public Sector, Commercial Media and Private Sector and Organic Media and the Plural Sector. In this view a healthy media ecology depends on the active participation of citizens as producers, creators and consumers of organic media. In order to flourish alongside for-profit and public offerings from private corporations and governments, organic media requires open, decentralised technology systems (owned by no one and everyone).

The authors I referenced agree that solving the ecological crisis is contingent on shifting our mental models, from a mechanistic view to systems thinking and ecological intelligence. As citizens, students, professionals or academics we need to look beyond the framework of conventional media ecology metaphors to include living systems. If media are an ecosystem that cultivates culture, we have both the right and the responsibility to "re-occupy our collective imagination". 12

Federico Gaggio is an independent strategist with a multidisciplinary background in philosophy, design, media and creative leadership. He is a co-founder and partner of the URGE Collective. He writes at ideas.gaggio.com.

Antonio Lopez, The Media Ecosystem: What Ecology Can Teach Us about Responsible Media Practice (2012). US: North Atlantic Books.

Lance Strate, Media Ecology: An Approach to Understanding the Human Condition (2017). Austria: Peter Lang Publishing. Strate provides a comprehensive overview of Media Ecology as a field of study.

Antonio López, Putting the Eco into Media Ecosystems: Bridging Media Practice with Green Cultural Citizenship. In Media and the Ecological Crisis (2014). UK: Taylor & Francis.

Gregory Bateson, Steps to an ecology of mind (1972, 1987). UK: Jason Aronson Inc.

Daniel Goleman, Ecological Intelligence (2009). UK: Crown Publishing

Antonio López, Putting the Eco into Media Ecosystems (2014)

Carlo Freccero, Televisione (2013). Italy: Bollati Boringhieri.

Antonio López, Putting the Eco into Media Ecosystems (2014)

Vandana Shiva, Monocultures of the Mind: Perspectives on Biodiversity and Biotechnology (London: Zed Books, 1993). Quoted in Lopez (2014).

Cory Doctorow, My McLuhan lecture on enshittification (30 Jan 2024)

Henry Mintzberg: Rebalancing Society: Radical Renewal Beyond Left, Right, and Center. (2015). US: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Antonio López (2012, 2014)